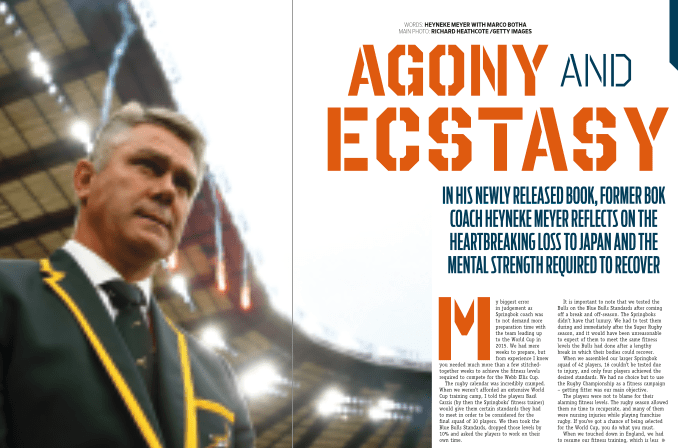

In his newly released book, former Bok coach Heyneke Meyer reflects on the heartbreaking loss to Japan and the mental strength required to recover.

[ed’s note: *Meyer’s book is available at all Exclusive Books, CNA, Bargain Books, independent stores, as well as online at Exclusive Books and Readers Warehouse; and retails at R295]

**These two combined extracts feature in the latest SA Rugby magazine

READ: What’s in our latest issue?

‘My biggest error in judgement as Springbok coach was to not demand more preparation time with the team leading up to the World Cup in 2015. We had mere weeks to prepare, but from experience I knew you needed much more than a few stitched-together weeks to achieve the fitness levels required to compete for the Webb Ellis Cup.

The rugby calendar was incredibly cramped. When we weren’t afforded an extensive World Cup training camp, I told the players Basil Carzis (by then the Springboks’ fitness trainer) would give them certain standards they had to meet in order to be considered for the final squad of 30 players. We then took the Blue Bulls Standards, dropped those levels by 10% and asked the players to work on their own time.

It is important to note that we tested the Bulls on the Blue Bulls Standards after coming off a break and off-season. The Springboks didn’t have that luxury. We had to test them during and immediately after the Super Rugby season, and it would have been unreasonable to expect of them to meet the same fitness levels the Bulls had done after a lengthy break in which their bodies could recover.

When we assembled our larger Springbok squad of 42 players, 16 couldn’t be tested due to injury, and only four players achieved the desired standards. We had no choice but to use the Rugby Championship as a fitness campaign – getting fitter was our main objective.

The players were not to blame for their alarming fitness levels. The rugby season allowed them no time to recuperate, and many of them were nursing injuries while playing franchise rugby. If you’ve got a chance of being selected for the World Cup, you do what you must.

When we touched down in England, we had to resume our fitness training, which is less than ideal. You want to arrive knowing that you’ve ticked all the necessary boxes.

On 19 September 2015, we played our opening match of the World Cup against Japan, a team coached by Eddie Jones. After they beat us by 34-32, their historic victory became known as The Miracle of Brighton.

On that day, we made tactical errors in our approach to the match, and while we scored four tries to three, we should never have let that match become as loose as it did. But tactics were not our Achilles heel. Fitness was.

Earlier, I quoted Vince Lombardi saying hard work always beats talent unless talent works. I believe this to my core.

The irony of The Miracle of Brighton was that we found ourselves on the wrong side of that very principle.

Eddie Jones had his side in camp from February to September 2015. Japan played in the Pacific Nations Cup in May and June before facing the Barbarians and the New Zealand Maori. After losing most of those games, there was a near full-on rebellion happening in Japanese rugby. But Eddie remained focused on improving his team’s fitness levels.

Japan’s devotion to work ethic in their corporate and labour culture was mirrored in their rugby. When they beat us, hard work beat talent because talent didn’t work hard enough. And for that, I take full responsibility. As Springbok head coach, it was up to me to demand more time to prepare the team for the World Cup, but I just didn’t bargain hard enough.

That said, had Japan recorded only that one remarkable victory, it could have been regarded as luck. But it was no miracle, and they again proved that in 2019 when they qualified for their first-ever quarter-final in a World Cup tournament, beating favourites Ireland along the way.

This time, with Jamie Joseph as their head coach, the Japanese team was again together from February to September. Their original plan was to recondition their players and then feed them back into Super Rugby. But when the Sunwolves lost their place in the tournament, Jamie decided to keep his players. The Sunwolves sent Japan’s second-stringers to New Zealand in June before the national side played warm-ups against the Kiwis, Aussies and Springboks.

I’m not telling you this to make excuses for what happened in Brighton. We failed that test on a tactical and fitness level. But Japan deserves credit as well, and the central element to their evolution as a Tier-1 rugby nation is their work ethic. If for no other reason, I believe they will continue to climb the ranks as a Test nation. The hardest lesson I learned from the Brighton match was to never compromise on work ethic.

I will never get over the disappointment of that defeat, and just when I think I’ve recovered to some degree, someone would ask me whether it still hurts. I’d laugh and tell them it didn’t any more until they had just reminded me that it still does.

I’m incredibly proud of the way the Springboks fought back after that disappointment against Japan, coming within two points of beating the All Blacks in the semi-final. I’ll discuss the rest of our journey in greater depth in the next chapter on mental toughness.

That All Blacks side was arguably the best rugby team to play in the professional era. And again, it’s not just talent that got them there. One of the reasons the All Blacks dominated world rugby the way they did between 2011 and 2017, was their fitness levels.

The All Blacks often had training camps, were fitter than any other international side, and they rested their players in the opening weeks of Super Rugby. The Crusaders are often said to be slow starters in Super Rugby, but that’s because they rest their All Blacks as part of a greater national strategy that prioritises the national team above all else.

In the previous chapter, I spoke at length about the agony of losing to Japan in our opening fixture of the 2015 World Cup in England. What I haven’t yet mentioned, was how proud I still am of the way the Springboks fought back to come within two points of beating the eventual champions in the semi-final.

I hear you – we didn’t win the tournament, so why go on about it? Because it would be dishonest of me to write a book of this nature and not also put on record my failings, disappointments and what I’ve learned from them.

When you leave a World Cup without the Webb Ellis trophy, it leaves a scar on everyone involved in the campaign. It also remains as a bitter afterthought in the collective memory of those who have supported you up to the point when you couldn’t give them one more round in the fight. That’s sport. That’s life. We all suffer disappointments.

In 2015, we had our issues, as I’ve mentioned. But we never threw in the towel. And therein lies one of the greatest lessons of my life. It comes without bells and whistles, without a trophy that stands to mark our effort. But for exactly those reasons, it’s worth telling.

At the post-match press conference after the Japan game, I knew it was up to me to be the light switch, however hard it was. I told the media contingent that we now only had to win six matches to lift the World Cup – a similar position to Rassie Erasmus’s four years later, and his team went on to do just that.

That night in Brighton, I didn’t want to go up to my hotel room. I sat speaking to our team manager, Ian Schwartz, discussing how we could turn this thing around. I was in actual fact just buying time to avoid having to sit with my own thoughts and heartbreak.

There are no words to describe how terrible I felt that day. We often spoke about the honour of representing your country, and I felt as if I had let my entire country down. I have said this before – I take losing personally.

I eventually went up to my room, swiped my card, and as the heavy hotel door shut behind me, I experienced the most extreme sense of loneliness I have ever known. After trying my best to be the team’s light switch in the hours following our defeat, I was now on my own, and what I saw in the mirror was a man the world hated and who had just himself to count on.

This was a sad state of affairs. But that’s honestly how I felt. If you devote your life to something you deeply love, the moments of joy and heartbreak spring from the same deep well of passion.

I remembered what my wife and sons had said to me – don’t apologise for the fire within you. And if this was how lonely my dream job made me feel, the only person who could get me out of this pit of misery, was me. I felt personally responsible for what had happened, and it was therefore up to no one else but me to turn this around …

I erected a large mirror just outside our team room, and before the players left, I asked each of them to go and stand in front of the mirror and appreciate the Springbok emblem on their tracksuits.

I told them: ‘We are the Springboks. The heartbreak ends here – we’re not out of the World Cup, we’ve got another six matches to play and win to become World Champions. We are the only people wearing the Springbok emblem on our hearts and it is up to every single one of us to embrace the pressure and turn it into something beautiful.’

Next, I had a meeting with our leadership group. In that World Cup, we had to use four captains as a result of injury – Jean de Villiers, Victor Matfield, Fourie du Preez and Schalk Burger. They, together with other senior players such as Duane Vermeulen, Adriaan Strauss, Francois Louw, Bismarck du Plessis and Bryan Habana came together to discuss the way forward.

After taking stock of what went wrong against Japan, I told the players that I was taking back full control of our tactics and that we would play and do exactly as I say. I had selected each one of them knowing what our strengths and weaknesses were, and their respective gifts as rugby players complemented a playing style that enhanced our strengths as a Springbok team.

Against Japan, we made ourselves vulnerable by selecting to play in a way that reduced our ability to apply pressure in the way we know best. Going forward, we were just going to be ourselves, and I needed them to trust me when I say our strengths will be more than adequate to carry us across the line.

The leadership group agreed, and we left the room with Japan behind us and with a renewed commitment to the ultimate goal we set for ourselves – to win the World Cup.

In the following weeks, we played some of the best rugby in my four years with the Springboks. We beat Samoa 46-6 (usually a very tough nut to crack), Scotland 34-16, USA 64-0, and in the quarter-finals, we defeated Wales 23-16. Our confidence also grew from a fitness point of view.

While we didn’t come into the tournament nearly as fit as we needed to be, the players understood the importance of putting in the extra effort as we neared the playoffs.

I’ll discuss our rivalry with New Zealand in greater depth … My final match against them was the semi-final of the 2015 World Cup. We were in the game and leading up until 10 minutes before the final whistle. But that’s when New Zealand are at their most lethal.

While one could try to make a case against strange decisions, a penalty try that wasn’t awarded, a yellow card that shouldn’t have been, a penalty that was turned around, and whatever else you can come up with to change the result in your head, that wouldn’t do justice to what the All Blacks achieved on that day, at that World Cup and in the preceding four years.

We hung in there for as long as we could. But ultimately, New Zealand won by 20-18, and I’ll concede that we didn’t only lose against the best team in the world in the preceding four years, but arguably also against the best sports team ever.’