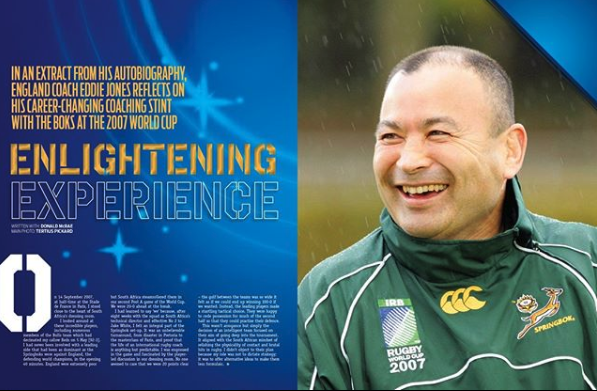

In an extract from his autobiography, England coach Eddie Jones reflects on his career-changing coaching stint with the Boks at the 2007 World Cup.

On 14 September 2007, at halftime at the Stade de France in Paris, I stood close to the heart of South Africa’s dressing room. I looked around at these incredible players, including numerous members of the Bulls team which had decimated my callow Reds on 5 May [92-3]. I had never been involved with a leading side that had been as dominant as the Springboks were against England, the defending world champions, in the opening 40 minutes. England were extremely poor but South Africa steamrollered them in our second Pool A game of the World Cup. We were 20-0 ahead at the break.

I had learned to say ‘we’ because, after eight weeks with the squad as South Africa’s technical director and effective No 2 to Jake White, I felt an integral part of the Springbok set-up. It was an unbelievable turnaround, from the disaster of Pretoria to the masterclass of Paris, and proof that the life of an international rugby coach is anything but predictable. I was engrossed in the game and fascinated by the player-led discussion in our dressing room. No one seemed to care that we were 20 points clear – the gulf between the teams was so wide it felt as if we could end up winning 100-0 if we wanted. Instead, the leading players made a startling tactical choice. They were happy to cede possession for much of the second half so that they could practise their defence.

This wasn’t arrogance but simply the decision of an intelligent team focused on their aim of going deep into the tournament. It also aligned with the South African mindset which relishes the physicality and brutal hits of rugby. I didn’t object to their plan because my role was not to dictate strategy; it was to offer alternative ideas to make them less formulaic.

My other responsibility was to support Jake. I would try to ease the pressure on him by offering tactical advice and another voice for the players, while also helping him deal with the media. The Springboks were much brighter than the clichéd stereotype of the South African rugby player. They were the opposite of the unimaginative hulks who clobbered anyone who got in their way but could be outsmarted by more thoughtful teams. I learnt that Jake, John Smit, Fourie du Preez, Victor Matfield, Schalk Burger, Bryan Habana, Jean de Villiers and the rest had an insatiable curiosity about world rugby. The way in which they grilled me about the attacking style we had developed at the Brumbies [between 1996-2001] was a clear sign of their open attitude and enquiring minds.

Jake and the players had given me the massive privilege of being a part of their team. It was an honour for which I will always be grateful. All I could think of was how best I could add value to help the team continue to improve. I had spent the last nine years scheming how to beat South African rugby teams. It was fascinating to now sit in the belly of the beast.

Jake and I had been good mates for more than seven years. I had first met him when he was part of a South African delegation, led by the then Springbok coach Harry Viljoen, who flew to Canberra in late 2000. They wanted to study the Brumbies’ new three-phase form of attack. Since Rod Macqueen had first invited me into his team way back in 1996, I have always been open to other coaches visiting my training camps. I don’t give away all my secrets but I think it’s in the spirit of rugby to share ideas. Jake and I stayed in touch and met as often as our schedules allowed. In November 2004, when the Boks and the Wallabies toured the UK, we swapped notes and helped each before we played England and South Africa faced Scotland. The previous week we had beaten the Scots and the Boks had lost to England. It was a really productive meeting and we both won the following Saturday. I also got a chance to see, first hand, the immense pressure Jake was under as Springbok coach.

South Africa presents an incredibly tough situation. While the country’s rugby followers expect to win most matches, with an intensity that boils around 90 percent, the head coach is probably only allowed to operate at 50 percent of his capacity. The politics of post-apartheid South Africa shadow the game and the Springbok team at every turn. But it’s inspiring to see the benefits of the development programmes, where black and ‘coloured’ (mixed-race) players emerged in the build-up to the 2019 Rugby World Cup. They have asserted themselves and demanded selection on the basis of their performances. South Africa is the sleeping giant of world rugby and could grow into an ever-greater superpower if they maintain their development programmes.

*Follow us on our new Instagram journey by clicking here

In 2007, my next job in rugby was meant to be as general manager and coaching adviser at Saracens. Mark Sinderberry and Nigel Wray had not been put off by my experience with the Reds and they had enticed me back to England to start working with Sarries from August 2007. Then, out of nowhere, Jake White called. We met up in Durban and, after a few days away, Jake asked if I would take a couple of sessions with the Boks. ‘Really?’ I asked. ‘I’d love to, mate.’ The idea of running around on a field with the Springbok players had me feeling like a kid on Christmas Eve. At the first session I watched them go through some shadow plays and I could tell they were pleased with how they were looking. I was relatively impressed with some aspects, but there were many areas of their play which could be improved.

We gathered in a circle afterwards and John Smit, as captain, addressed his boys. He was complimentary and then he looked over at me. ‘What do you think, Eddie? How was that?’ ‘It wasn’t bad, mate, but if I were giving you a score out of 10, I’d say it was about a four.’ John looked at me. He was checking to see if I was joking. ‘A four?’ ‘Yeah, mate. There’s a fair bit to work on.’

It was true. They deserved little more than a four because of the talent that was on the field. They had so much more in them. I’ve never been one to pull my punches and I didn’t really care if they were offended. John had asked me my opinion and I had given it to him. I went through some set moves and showed the Boks how I would do things differently. We did more of the same at the next session and they must have liked it because Jake made me an intriguing offer. Would I consider staying on with the Boks until the end of the World Cup as their technical adviser?

As the words came out of his mouth, I tried to stop myself from giving Jake a hug. A technical adviser to this group of players on the eve of a World Cup? Seriously? It’s hard to describe just how excited I was by the offer. Here was Jake offering me the chance to be involved in a team that clearly had the potential to go all the way. I had done none of the heavy lifting of the previous years and now, with the tournament in touching distance, I was invited along for the ride.

Once my role with the Springboks had been agreed, I couldn’t wait to get started. I was surprised to find the team so well versed in the rugby I had developed with the Brumbies and Wallabies. It was fascinating to hear Smit reveal that the structure of the Bok attack was built on our Brumbies template. After training and over shared meals and a few beers, they quizzed me about the rugby that had been born and built in Canberra. In my experience, only the Brumbies could match these Boks when it came to an intellectual curiosity about the game. I already knew that Victor, Fourie, John and the leading Boks were great players. I discovered that they were great men as well. At one of our first meetings Victor came up to me and said, ‘We want to play much closer to the gainline. Do you remember that five-man lineout you had with the Brumbies? Where you had the wing at the front of the lineout? I think that would suit us.’

We spoke frankly and I added another element to the Boks – particularly in terms of their backline play. I had been fortunate to coach George Gregan and Stephen Larkham for so long and Fourie and Butch James, as the Springboks halfbacks, were like sponges when I spoke to them about playing flat, counter-attacking rugby. It enabled them to create an attacking game that suited their strengths. Their game was based on savage defence. Their attacking plays tended to be pieced together from other teams. They were on the right track but we could help them become gainline focused. We needed Fourie and Butch to have a clearer vision of playing flat against the line.

The second flyhalf in the squad was Andre Pretorius. He was a talented but flighty player. To win the tournament we needed a solid guy playing like a modern-day Henry Honiball. In my opinion, Butch was that man. In consultation with Jake, we tinkered with the alignment of the backs as the Boks tended to play very deep. We got them playing flatter behind that big pack. It was simple stuff and the Boks took to it with conviction. Jake and I just clicked. We had a mutual obsession with rugby. We also liked each other’s company and loved working hard on improving a squad of players. I think I helped Jake in two obvious ways. As an outsider, coming into such an established set-up, I could see the big picture much more clearly. Jake had coached guys like John and Fourie from U19 national level and, while they appeared close, there were tensions and disagreements. For the players, my arrival meant they had a new sounding board.

They spoke to me in a way that they could not have done with Jake. I was much more relaxed than Jake, or how I would have been if I had been their head coach, and so we had a terrific relationship. There was not a single player I did not get on with in the Springbok squad. I was not responsible for selection and so they could just be themselves with me and ask for advice in a totally open way. I also tried to ease the media pressure and expectations on Jake. It helped that I had been all the way to the World Cup final four years earlier and I could pass on some of the lessons I had learned about preparation and tension. When my Springbok experience ended, I vowed that if I was ever to start again as a head coach in the Test arena, I would always have an independent guy, a righthand man, who is not directly involved in the coaching.

READ: What’s in our latest issue

The World Cup final on 20 October 2007 was an even less attractive game than the taut and tense battle from four years before. A couple of tries were scored in 2003, but South Africa and England fought out a tryless grind on a chilly autumn evening in Paris. To the neutral, the rugby probably seemed cold and clinical, shaped by pragmatism from both sides, but Jake and I liked the way the match unfolded…. After an hour the Boks were ahead 15-9 and we shut England down. The score did not change for the rest of the game because we played smart, percentage rugby. It was not a game to live long in the memory of the casual fan. But I admired the way the Boks had played so intelligently and efficiently. And I was thrilled for the men to whom I had become so close in such a short time. They were world champions.