World Rugby’s zero-tolerance approach to high tackles aims to protect the tackler and the ball-carrier. SIMON BORCHARDT reports.

On 14 December 2016, World Rugby announced details of its zero-tolerance approach to high tackles, which would apply at all levels from 3 January 2017.

In a bid to reduce injury risk, World Rugby introduced minimum on-field sanctions for reckless and accidental contact with the head in a bid to lower the height of the tackle. A reckless tackle would result in a minimum sanction of a yellow card and a maximum sanction of a red card, with these sanctions applying even if the tackle started below the line of the shoulders. If a player made accidental contact with an opponent’s head, either directly or where the contact started below the line of the shoulders, the minimum sanction would be a penalty.

World Rugby’s directive came after an extensive research study in which 611 head injury assessment (HIA) incidents were reviewed from 1 516 elite matches between 2012 and 2015. The results showed that 76% of all head injuries occurred in the tackle, while 72% of HIA incidents in the tackle occurred to the tackler (making the tackler’s risk of head injury 2.6 times higher than the ball-carrier’s). The study also found that body position, speed and the direction of tackle all influence the risk of head injury in the tackle.

South African sports scientist Prof Ross Tucker played a significant role in the study. Before joining World Rugby in 2015 as a science and research consultant, he worked with a number of teams, including the Blitzboks, in high-performance sport. Tucker is involved in World Rugby’s player welfare division, which is part of the technical services department, and the competitions and performance division, which sees him provide scientific and analytical support to tier-two rugby nations. He also sits on World Rugby’s law committees, focusing on whether a law change is having its intended effect.

Fifteen months after World Rugby’s ‘zero-tolerance’ directive, Tucker sits down with SA Rugby magazine to discuss the rationale for the directive and its impact on the game.

THE CONCUSSION ASSESSMENT TOOL

At the 2003 World Cup, there were only four reported concussions. That’s not because there were only actually four concussions in the 48 matches, but there was no tool in place to monitor and identify concussions when they happened. And then when a concussion was diagnosed, the player was forced to sit out for three weeks unless a neurology specialist cleared them to return sooner (paradoxically, this safety initiative pushed concussion ‘underground’). World Rugby’s HIA process was introduced in 2012 and at the 2015 World Cup there were 24 diagnosed concussions.

The English Premiership has kept a record of concussions since 2002, far longer than any other professional rugby competition. In 2012, the year the HIA was introduced, there is a spike in the number of concussions. Again, that’s not because there were more concussions than in previous years, says Tucker, but rather because clubs had an incentive to take a concussed player off

the field. They also had guidance in making the diagnosis thanks to the HIA process, and there was increased awareness of concussions.

‘Before the HIA, a player would only come off the field if it was a clear and obvious concussion, requiring unavoidable replacement,’ he explains. ‘The HIA gave teams an opportunity to test for concussion, because they could bring on a temporary substitute for 10 minutes while a player was being assessed. The threshold to diagnose concussions is now lower.’

Shortly after becoming World Rugby chief medical officer in 2011, Dr Martin Raftery worked out that a team doctor had an average of 64 seconds to run on to the field, diagnose an injured player and decide whether they should be replaced. As a consequence of that limited time, 56% of players who were diagnosed with concussion after the match had carried on playing.

‘That is obviously a problem, because an injured player is not being managed optimally and there’s a risk of a player taking a second impact to the head,’ says Tucker. ‘The solution was to “buy” time and knowledge. World Rugby had to give the doctor enough time in which to make a proper diagnosis and a tool he could use to systematically evaluate whether or not a player was concussed. The HIA is that tool.’

The HIA sideline assessment is a modified version of Scat5, a sports concussion assessment tool that comes from the world consensus concussion group and is considered the best method of assessing someone for concussion.

‘The HIA process starts with the team and match-day doctors looking for observable signs like suspected loss of consciousness, confusion, convulsions and balance disturbance/ataxia,’ Tucker says. ‘These are called criteria-one signs, and if any one of 11 such signs is evident, there’s not even an off-field assessment, the player goes off and doesn’t come back on.

‘If those signs are not observed and diagnosis is not apparent, but there is suspicion of concussion, a player is removed for no more than 10 minutes for an off-field screen. This begins with a series of questions to test the player’s basic awareness and cognitive state, including asking what venue he is at, what half of the match it is, which team scored last and so on.

‘Then there is a memory test in which the player has to repeat a list of five words back to the assessor and a concentration test where they recite a list of digits backwards. For instance, the assessor says “3-8-1-4” and the player has to respond with “4-1-8-3”. This list gets up to six digits long.

‘There’s also a balance test, a symptom checklist and a test of delayed memory. In other words, it’s a multimodal test that assesses a range of brain functions, because concussion can affect any one of them.

‘If a player performs worse than their baseline – assuming they’ve done a test for comparison earlier in the season, which most professionals will have done – or if they perform worse than identified target scores for each test, they have an abnormal HIA off-field screen and their substitution becomes permanent.

‘A second HIA test is then done after the match on the same day within three hours of the injury and a third HIA 36 to 48 hours after the match, and it’s on the basis of those two tests that the concussion is diagnosed.’

All HIA tests are sent to World Rugby as part of the HIA process. Tucker says that over time, it may be possible to improve the test and World Rugby is sponsoring research to identify which components, or if new tests, such as eye tests or reaction-time tests, are more effective at diagnosing concussions.

‘No tool is perfect, but we’d like to get the sensitivity of the HIA process close to 90%. You don’t want concussed players to carry on playing, but you don’t want players who aren’t concussed to be taken off the field wrongly either. That’s the balance that must be sought.’

THE RESEARCH STUDY

World Rugby’s research team, led by Tucker, studied 611 incidents that resulted in HIAs and compared them to more than 3,500 tackles that didn’t cause head injuries.

The most significant discovery was that 335 HIA injuries occurred while making a tackle and 129 while being tackled.

‘That was surprising and challenging from a legal perspective, because the law is almost exclusively written to protect the ball-carrier, who is on the receiving end of most instances of foul play,’ says Tucker.

The research team then looked at why the tackler is 2.6 times more at risk of a head injury than the ball-carrier, with every analysed tackle scored according to 20 or so factors, including the following:

• Relative speed of players: Backline players are twice as likely to get injured while making a tackle than forwards, probably because backs tend to engage in higher speed tackles. High-speed tackles are more dangerous than medium-speed tackles, which are more dangerous than static tackles.

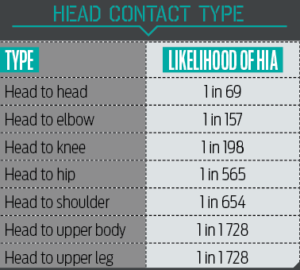

• Nature of the head contact in the tackle: Was it head to head, head to shoulder, head to hip, head to knee, etc? Head to head contact is six times more risky than head to hip contact. The ideal target for the tackler is between the sternum and the waist of the ball-carrier. Overall, the risk of injury is 4.3 times higher for legal tackles with higher contact (shoulder and head to head) than legal tackles with lower contact (below the shoulder).

• Body position of the ball-carrier and tackler: Were they upright, bent at the waist or diving/falling? As either of the players can be in one of three positions, there are nine possible combinations. The most injuries occur when both players are upright. The lowest risk for the ball-carrier is when he is bent at the waist, no matter what the tackler does. For the tackler, the risk is lowest when diving and highest when upright. ‘The key message here was that an upright tackler is the situation we want to avoid, because it is higher risk and happens quite often,’ says Tucker. ‘The safest tackle is one where the tackler is bent at the waist or diving.’

• Type of tackle: Was it an active or passive shoulder or a smother tackle? The research team then produced a spectrum of risk, and worked out which type of tackles were more and less likely to cause a head injury. ‘Once we knew that, we could look at substituting high-risk tackles with low-risk tackles,’ says Tucker. ‘One way to eliminate high-risk tackles would be to ban tackling, but obviously that’s not an option. That would be like banning cars to prevent car accidents. Instead, we wanted to look at ways to shift behaviour away from high risk towards low risk. That meant, for instance, getting tacklers lower and bent at the waist, lowering the speed of the tackle, or having fewer front- on tackles. Of course, some of these are feasible, others are not, and our challenge was to identify where a difference could realistically be made. That’s where the expert multidisciplinary working group came in.’

THE WORKING GROUP

Once the team had completed its research, World Rugby convened a working group that included coach Eddie Jones, referee Alain Rolland, former Scotland captain John Jeffrey, Ireland lock Paul O’Connell, former Argentina captain Agustín Pichot (who is vice-chairman of the World Rugby board) and other independent experts. Tucker presented the research team’s data to them over two days in Dublin.

‘They said they wouldn’t try to change the focus on active shoulder tackles and front-on tackles, because that would be changing rugby,’ he recalls. ‘They said we should try to get tackles lower and players from an upright position to a bent at the waist position. Speed, acceleration and tackle technique could all be looked at in the future.’

The key point was that getting the tackler lower and into a bent at the waist position would protect both players. The ball-carrier would be protected because his head would now be ‘safe’ in the sense that there should be no direct contact to his head if the tackle is lower. The tackler, on the other hand, would be protected because his head would be more likely to make contact with the ball-carrier’s chest, trunk or waist, which the data had shown was much less likely to cause injury than the head.

‘Basically, lower tackles remove the ball-carrier’s head from danger and prevent the tackler’s head from being in the “air space” of the ball-carrier’s head, which is his most dangerous scenario,’ says Tucker. ‘So the change would protect both players, which was really important given that almost three-quarters of the injuries are to the tackler. It’s just that the law had to be written as though the ball-carrier was the player we were trying to protect. He wasn’t. It was the tackler all along.’

The working group’s theory was that by having a zero-tolerance approach to high tackles and head contact, players would be compelled to go lower to avoid punishment. Every incident that had previously been just a penalty would be a yellow card and previously a yellow card would now be a red card. The exception would be accidental high tackles when the ball-carrier slips or ducks, which would just be a penalty.

‘You can use a carrot or a stick to change behaviour,’ says Tucker. ‘This was the stick.’

THE IMPACT ON THE GAME

After the zero-tolerance directive from World Rugby, the number of high-tackle penalties increased by 64% from 2016 to 2017 and yellow cards jumped 41%.

‘That’s encouraging because it means referees are being harsher on high tackles,’ says Tucker. ‘They recognise and penalise them more now than before. That’s the case in every single top rugby competition around the world, although it increased more in some competitions than others.’

However, while these increases have created greater awareness around protecting the head to prevent concussions, a dose of perspective is that there is still only a yellow card every 10.9 matches. Tucker wonders whether this is frequent enough to act as a proper deterrent.

‘You’re only going to change players’ behaviour if there’s an incentive – or in this case a disincentive – to change. That disincentive takes the form of sanction – penalties and cards – that must be frequent and strong enough, otherwise why would a player pay attention to it? It’s like giving a drunk driver a stern warning and a small fine – it’s not enough to compel them to change their behaviour.

‘Yes, there has been a 41% increase in yellow cards, which is good, but is it enough, given how infrequent they are? Obviously, the flip side to this is that the referees don’t want to ruin matches they officiate. They juggle a requirement to ensure player safety and a fair and entertaining contest. If multiple yellow cards were being given out every match, it would detract from the latter, and World Rugby appreciates this “tension” for the referees.’

That said, as it stands, Tucker dismisses concerns from fans and the media that yellow cards are ‘killing the game’, with just one yellow card every 10.9 matches.

He also points out that a high-tackle penalty is accompanied by a card only once every eight occasions. In other words, a referee will award eight high-tackle penalties before issuing a card. This is compared to a card every three deliberate knock-on penalties. A player is therefore 2.6 times more likely to be sent off the field for a deliberate knock-on than a high tackle. He is also 2.5 times more likely to be carded for not retreating 10m than for a high tackle.

‘I understand why this is the case,’ says Tucker. ‘An intentional knock-on stops the game and is easier to judge, because a referee only has to ask one question: Did the defender have a realistic chance of catching the ball? If he didn’t, it’s a yellow card. It’s a similar situation with a spear tackle, where you see the referee’s process involves two considerations: Did the player’s shoulders go above the horizontal? How did he land?

If it’s yes, and the player came down on his head, it’s a red card. It’s a simple decision framework. High tackles are more fluid. Play can continue and there could be three tackles in three seconds, and the referee needs to focus on the next one, so I understand why many may be missed, or sanctioned a level below where perhaps they should be.’

Another interesting statistic is that of all the yellow cards awarded in professional rugby in the past three seasons – a total of 2 065 – 8.9% were for high tackles, 7.5% for collapsing the maul and 7% for deliberate knock-ons.

‘The point is that high tackles account for one in 11 yellow cards. People’s perception is that it’s gone way overboard. The data would suggest it has not,’ says Tucker.

Indeed, penalties are far more likely for other infringements.

‘A tier-one Test team averages 4.5 breakdown, two scrum, 1.5 offside and 0.5 high-tackle penalties per match. If I’m a coach, what is going to be my focus? I’m not worried about half a high tackle penalty every match, I’m far more worried about the breakdown, the scrum and staying onside. So we have to ask the question: Do we need to make high tackles more frequently penalised, keeping in mind that only one in 11 of all yellow cards are for high tackles and that high-tackle penalties happen only once a match, on average?’

Tucker believes taking even stronger action against high tackles will ultimately be a small price for rugby to pay.

‘If the perception of rugby goes the way of American football, which is seen to be a dangerous sport, participation numbers will drop because parents won’t want their children to play the game. We have to prevent that from happening. Doing so will not make the game “soft”, as some have suggested. You can still tackle a guy so hard his fillings fall out. Just leave his head alone.’

REFEREE’S VIEW

‘Firstly, I am very much in favour of ensuring players’ safety and protecting the integrity of the game,’ former Test referee Jonathan Kaplan tells SA Rugby magazine. ‘The principle of World Rugby’s zero-tolerance approach to high tackles is 100% correct. However, it will only be good for the game if it is able to protect the players and keep the function of the game intact.

‘I think referees have done well with the obvious, upper-end type of tackle, which results in yellow or red cards, although the judiciary hasn’t always fronted up in these cases. But I don’t think the less obvious, lower-end type of tackle has been refereed well at all. There have been gross inconsistencies regarding contact with the head this year, including cleanouts at the ruck. Some have resulted in a yellow card, others in a red, and others not spotted at all by the referee, assistant referees and the TMO.

‘I believe officials should be able to use common sense when adjudicating on high tackles. Chiefs replacement flank Lachlan Boshier, against the Crusaders, and England wing Anthony Watson, against France, were yellow-carded for high tackles on a diving try-scorer in the corner. Penalty tries were also awarded on both occasions.

‘Neither player intended to go high, they did all they could do to protect their tryline. The referees, however, had no choice but to give a yellow card and award a penalty try, according to the law. I would like World Rugby to trust referees to use common sense in cases like this by awarding a penalty try – as a try probably would have been scored but for the high tackle – while allowing the offending player to stay on the field. No one, not even the Crusaders, thought Boshier deserved to be yellow-carded, yet he was and the Crusaders scored two tries while he was off, to comfortably win a game that had been heading for a close finish.

‘When it comes to high tackles, referees should be allowed to make decisions they believe are in the best interests of the match, as they are allowed to do in other areas of the game. If the referee has been trained well enough, he will use common sense to make the correct decision 98 times out of a hundred.’

– This article first appeared in the May 2018 issue of SA Rugby magazine. The June issue is on sale 21 May.