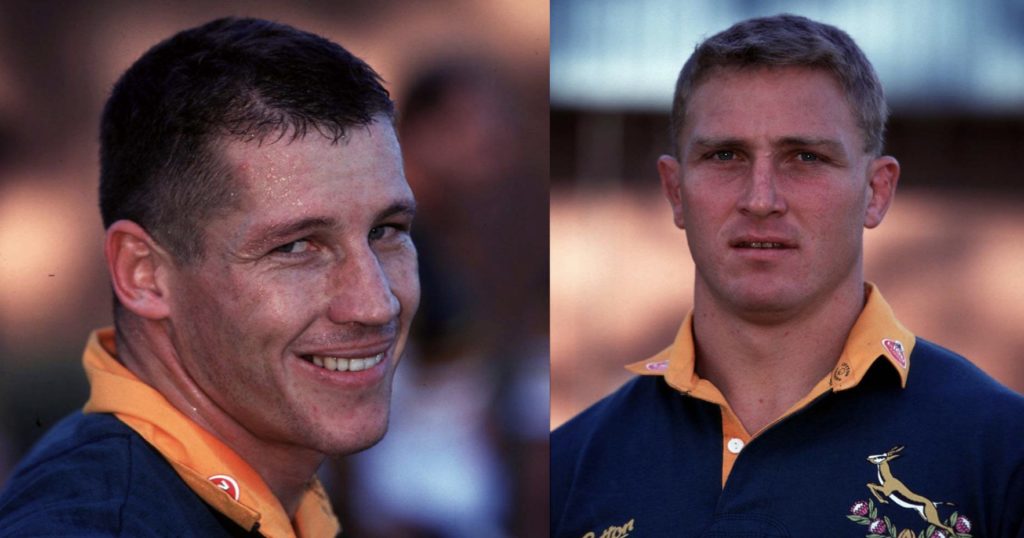

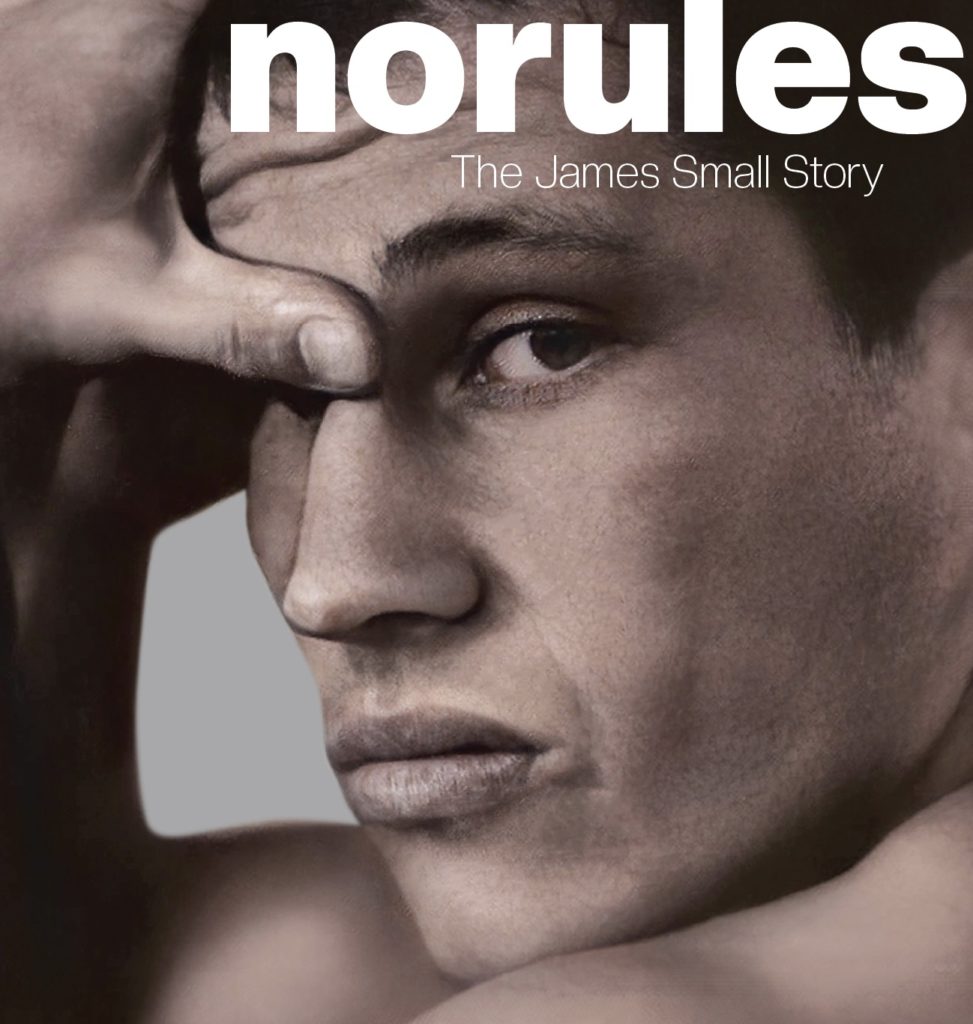

In an extract from No Rules – The James Small Story, Japie Mulder recalls his verbal battles with the winger, and what happened when Small swore at Bok teammate Johan Ackermann.

I met James when we played in the Transvaal U20 trials at Sturrock Park, the old police fields in Johannesburg in 1989. I knew of him because he’d already played for the Transvaal senior side, but I didn’t know him.

James was clearly very talented. He had ball skills from soccer, he was physical, strong and quick – he had it all. One of the first things I noticed him doing differently was the way he dealt with up-and-unders. When they kicked them on you in those days you’d always shout ‘my ball’ but he instead shouted ‘James’ ball’, which I found quite funny.

We played together for the first time against Western Transvaal at Ellis Park later that year. I was playing in well-worn Patrick boots as I was a student and couldn’t afford new boots – it was still the amateur era. James, who was already being sponsored by Adidas, sat next to me in the change room before the captain’s run on the Friday evening, took one look at my boots and said, ‘Not a fuck are you running out and playing in those!’

So he gave me his pair. They were the first boots I received for free and were almost brand new; I don’t think he’d had more than one training session in them. He told me not to worry, he had another pair.

That year, Transvaal U20 won the Midas Cup. We played the final as a curtain-raiser to the 1989 Currie Cup final between Western Province and Northern Transvaal. We beat a very strong Northerns team in our final – several of their players, like Johan Roux and Philip Schutte, went on to play top provincial rugby and for the Springboks. We had quite a lekker backline, with James and Pieter Hendriks in it.

Initially, the Transvaal players saw James as an enigma. He was an Engelsman in a team with a strong Afrikaans culture and a rebellious Engelsman to boot.

He wasn’t an approachable guy and he was always late for training and meetings. But everyone knew he could play the game and that’s what mattered.

I always got the impression that everyone knew they were never going to change James. Even in those early years at Transvaal, there was a feeling that the more you tried to get him to toe the line, the worse he became. It was like an attitude of ‘Don’t go there, let someone else sort him out, we can’t work with the oke.’

James and Hennie le Roux had some big clashes, even though Hennie was supposedly also an English-speaking guy. To this day I don’t know if his first language is Afrikaans or English! Hennie was the type of guy who was exact, so he’d say he wanted the ball to come to him at a three-degree angle or something like that, and James would say, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’ James was more like me, in that you play the game as you see it. We believed everything couldn’t be completely planned and rehearsed.

I think James much preferred the Natal culture when he moved to Durban at the end of 1992. At Transvaal we were regimented and disciplined. Like, ‘Jy moet stil bly op die bus [you must be quiet on the bus]’. It was all, ‘Ja meneer, goed meneer [yes sir, very well sir].’ That’s how you showed respect to the coaches.

I couldn’t believe the difference in culture when in 1993 I went over to the Boks, who were being coached by Mac (Natal’s Ian McIntosh). There was music on the bus, and the guys were smiling and laughing. I thought to myself, ‘What the hell, do these okes know we are playing a Test match in the next hour?’

So that’s probably why James enjoyed it so much at Natal. He just never fitted into the Transvaal culture. If you were late at Transvaal, you were dropped. James preferred a culture where there’d be some sanction if you were late but you wouldn’t get dropped. At Natal I think it was a case of ‘Why were you late?’ Then after James gave his answer, he’d be told he was a naughty boy and he mustn’t do it again, but life would go on. It didn’t work like that at Transvaal.

James wasn’t the kind of guy who’d approach you, so I approached him. I think I hit it off with him more than the other Afrikaans guys did because we were like kindred spirits and enjoyed each other’s company.

I also enjoyed the fun side of things and I’ve always liked guys who are a bit rebellious.

When I was in business with (former Springbok hooker) James Dalton, a lot of people said, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ and I’d say, ‘He’s a good oke’. Maybe my failure to see anything but good in people is my weakness, but I believe in giving everyone a fair chance.

James probably had more enemies than friends because of his on-field mannerisms, but if you really got to know him off the field, he was very different. You needed to get to know him and be trusted by him.

Those who never got close to him thought he was arrogant, but he really wasn’t. He had this front of being a breker and naughty boy. OK, he was naughty, but once you spent time with him, you realised how humble he was.

I started playing Transvaal senior rugby in 1991 and also played with James in 1992. At the end of that year he left for Natal, so I ended up playing a lot of my rugby against him.

Let me tell you it was a very different experience to playing with him. James was a great guy when you were wearing the same jersey as him on the rugby field, but wear a different jersey and it was like waving a red flag at a bull.

James had a big mouth on him and he could get into your head. You always knew he was going to come at you, calling you a ‘dumb Dutchman’, and of course we gave it back to him, calling him a ‘soutpiel’.

Even though we were good mates off the field and playing together for the Boks, James and I had a few serious altercations.

One of them was in 1996 when Transvaal played Natal at Kings Park. James was having a full go at everybody, like he always did. They scored a try and he jumped up in front of me and shouted ‘Yes!’ and I said ‘What?’ He pushed me and I fell over Natal lock Mark Andrews. I went mad and tried – unsuccessfully – to get hold of James for the rest of the game. He’d definitely got into my head.

At the final whistle, he came over to shake hands and I told him to bugger off.

Three weeks later, we played Natal again, at Ellis Park, and I was determined to get my revenge on James. This time I managed to get it right. I got him at the bottom of a ruck and he left the field needing stitches. He was furious and had a full go at Ray Mordt, our coach. ‘Is that the way you coach your players to play rugby?’ he barked.

In those days, rugby was very physical and you abused the opposition physically and verbally on the field. It’s just the way it was. The referees didn’t stop it, whereas now I get the impression they shut things down very quickly.

James won a lot of psychological battles where he’d suck an individual player from an opposition team into just focusing on him while there were another 14 players giving that player’s team a hiding. Okes would lose the plot.

Some guys could get into James’ head and also make him lose the plot a bit, but I think that inspired and motivated him.

James was a funny character on the field in the sense that he had so much passion, but sometimes when things weren’t going the team’s way, he’d seemingly lose interest.

In 1996, the Springboks played the Wallabies in Sydney. Late in the game, when we were losing and nothing was going right for us, James was sitting on his haunches looking at the crowd, paying no attention to what was happening on the field.

I shouted, ‘James, you have to defend now! What the hell are you doing?’

He shouted back: ‘Fuck you okes, man!’

He hadn’t got the ball the whole game so he was very upset.

But that was James. He was passionate, which may have been his problem.

During that Test match, he swore at Johan Ackermann, the big Bok lock, because he wasn’t getting any ball.

I remember thinking ‘S**t, don’t do that!’ but nothing happened on the field.

After losing the Test, we arrived back at our team hotel in Manly, a seaside resort suburb of Sydney, in a bad mood. I ended up sharing a lift from the hotel reception up to the floor we were staying on with James, Johan and one of the props.

As the door closed, Johan grabbed James by his collar and pulled him closer: ‘Listen Engelsman, if you ever talk to me like that again, I will kill you.’

The tears were running down James’ face when he humbly apologised.

‘Ackers, I’m sorry, it was on the spur of the moment, I was just upset,’ he said.

Johan accepted his apology, they shook hands, and we moved on.

No Rules – The James Small Story, as told to Simon Borchardt and Gavin Rich, is available to order at jamessmall.co.za. Book proceeds will go to The James Small Trust, which provides James’ children, Ruby and Caleb, with financial assistance for their education.

Photos: Duif du Toit/Tertius Pickard/Gallo Images